State Data

Confidence in data for this state:

MODERATE

2018 data unless noted.

Definitions

Terms used on this website and in data sets are defined & discussed here.

Biosolids being delivered for land application, as part of the Biosolids Farmland Application Program at Nebraska Extension. Photo courtesy of the Institute of Agriculture and National Resources, University of NE Lincoln.

Biosolids being delivered for land application, as part of the Biosolids Farmland Application Program at Nebraska Extension. Photo courtesy of the Institute of Agriculture and National Resources, University of NE Lincoln.

Biosolids ready for land application, as part of the Biosolids Farmland Application Program at Nebraska Extension. Photo courtesy of the Institute of Agriculture and National Resources, University of NE Lincoln.

State Statistics Dashboard

State Summary

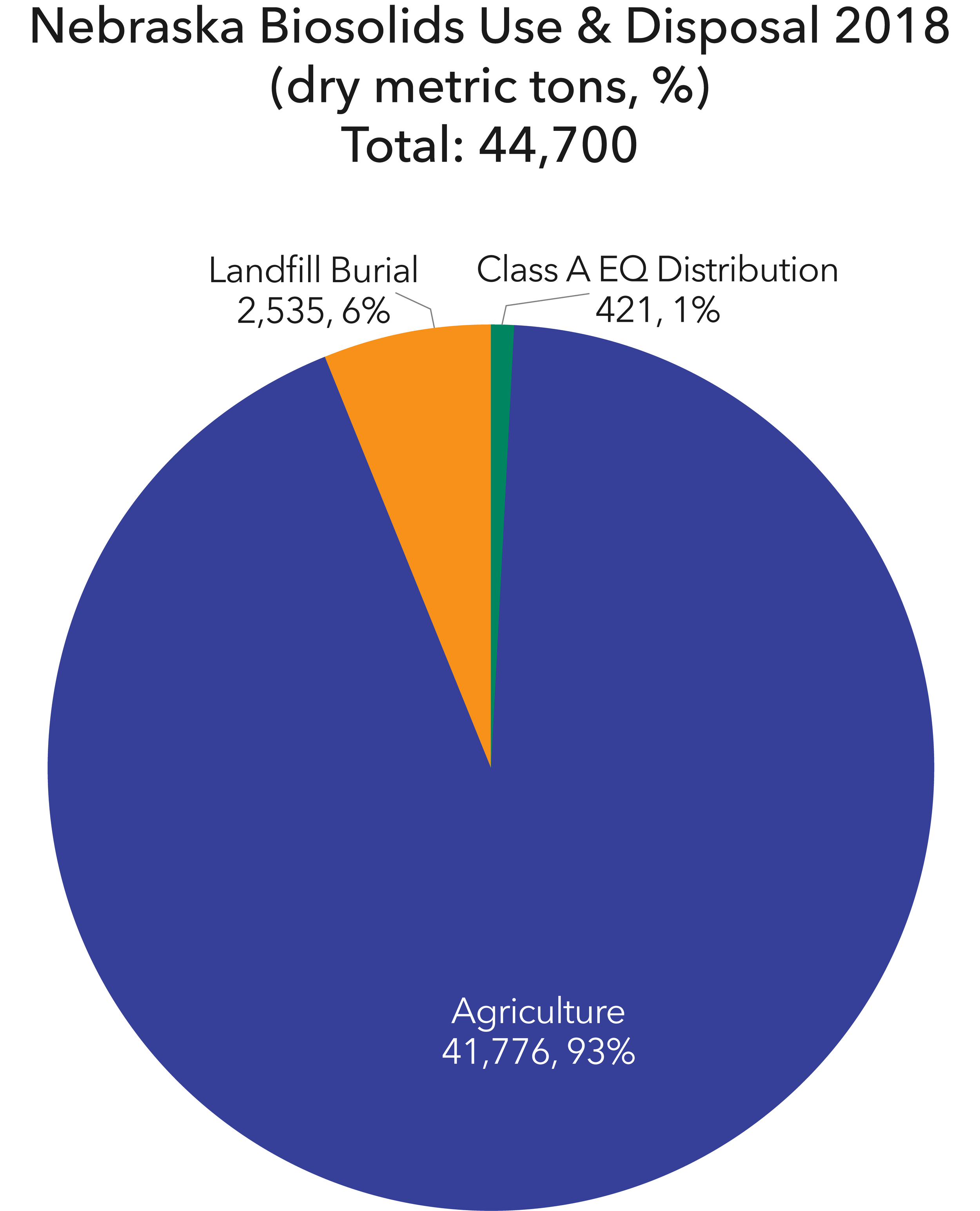

● Nebraska has a robust agricultural economy and millions of acres of farmland, making land application an easy and affordable option for biosolids management. Each year, including in 2018, the vast majority of Nebraska biosolids are treated to Class B standards and land applied.

● The Department of Environment and Energy (NDEE) issues NPDES permits to water resource recovery facilities (WRRFs) and requires facilities to get approval for land application of biosolids, but the federal biosolids rule (40 CFR Part 503) is administered by U.S. EPA Region 7. Nebraska has no specific requirements for biosolids management beyond Part 503, though permission for land application may not be granted by NDEE if state setback requirements and agronomic loading rates (also applicable to treated effluent) are not met.

● Omaha, Nebraska’s biggest city (population 486,000), has two main WRRFs: Papillon Creek “Papio” WWTP and Missouri River WWTP, which also serve surrounding communities, including Bellevue (population 64,000). The facilities receive wastewater from the large meat-packing industry in addition to domestic wastewater; for Missouri River, that makes for a total flow equivalent to >600,000 people. Both facilities have anaerobic digesters and capture biogas to fuel engines and produce electricity; 67% of Missouri River’s and 35% of Papio’s electricity demand is met this way. Biosolids from both WRRFs are land applied on local farmland where corn is grown for animal feed and ethanol. Omaha has almost 37,000 acres permitted for land application. In 2018, a small amount of Omaha biosolids were disposed of in the municipal landfill. The massive floods of 2019 crippled the Missouri River WWTP for several months.

● Lincoln, the state’s capital, and second-largest city (population 291,000), has two WRRFs. Both facilities use anaerobic digestion to treat biosolids to Class B standards for use as soil amendment or fertilizer. Biosolids from the larger Theresa Street WRRF are dewatered and spread on nearby private farmland. Biosolids from the Northeast WRRF are injected in liquid form in cropland owned and managed by the city; profits from the sale of these crops help fund water resource recovery. Methane from the Northeast WRRF’s digesters is captured and used to generate electricity and heat. As of 2021, methane from the digesters at Theresa Street is captured, cleaned, and piped to a nearby utility border station as renewable natural gas (RNG). After being sold on the national market by a third party, most of the revenue from the RNG and energy credit sales go back to the city of Lincoln. Lincoln’s biosolids land application program started in 1992 and receives support from the University of Nebraska Extension.

● Kearney and Fremont also have anaerobic digesters and produce renewable electricity from the biogas. Both recycle biosolids to soil, although, for 2018, Fremont reports having stored its biosolids, which was unusual.

● Grand Island, the state’s 4th largest city (population ~50,000), treats 70% domestic and 30% agricultural industry wastewater. Its solids are dewatered with belt filter presses and sent to landfill.

● Beatrice (population ~13,000) has successfully composted its biosolids for a long time (https://wasteadvantagemag.com/a-30-year-partnership/).

● Septage can be land applied in Nebraska if management practices, setbacks, slope, agronomic loading rate, and other state and federal requirements are met.