State Data

Confidence in data for this state:

MODERATE

2018 data unless noted.

Definitions

Terms used on this website and in data sets are defined & discussed here.

Biosolids land application. Photo courtesy of NEBRA.

State Statistics Dashboard

State Summary

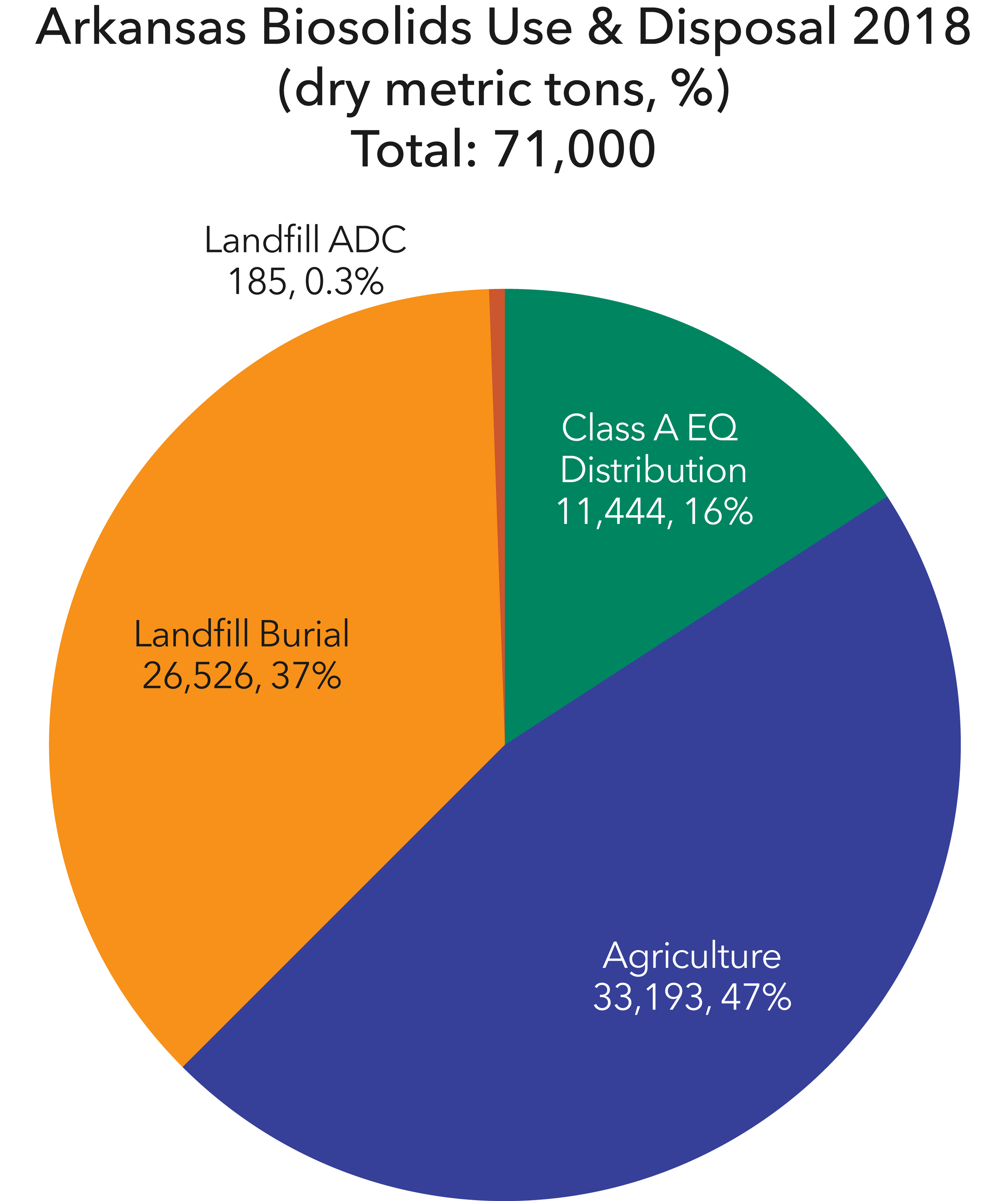

● About 2/3rds of Arkansas biosolids are applied to agricultural or other lands to support local farms and crops. As noted by the AR Division of Environmental Quality (AR DEQ), “1000s of acres are land applied to – e.g. one contractor has 50 permits, over 600 acres per permit (but not all for biosolids, other types of waste too). Some smaller communities landfill, who don’t have land application permits nor contractors to handle [their wastewater solids].” Much of the land-applied biosolids are liquid slurries pumped from lagoons, which are common for wastewater treatment in Arkansas. These biosolids are mostly Class B, treated in a few places (e.g. Little Rock) with anaerobic digestion or alkaline stabilization, but mostly by aerobic digestion. Some Class A and EQ biosolids are produced by heat drying (e.g. Fayetteville) and composting (e.g. Hot Springs). No incineration of wastewater solids occurs in Arkansas.

● Roughly half of the state’s public water resource recovery facilities (WRRFs) manage their solids with their own staff, and about half contract with private companies to manage their land application, complying with state and federal regulations. Contracted biosolids management companies active in AR include HydroAg, Denali Water Solutions, Mannco, and Synagro.

● AR DEQ regulates biosolids land application, applying state guidance that is similar to the federal U.S. EPA Part 503 regulations, but with additional setbacks and nutrient management and other requirements.

● In the early 2020s, AR DEQ is writing Rule 34, which will cover all land application of domestic and industrial wastes not already covered by Rule 5, which largely governs liquid animal waste (CAFOs, etc.). According to AR DEQ, the agency “wants a rule to be able to defend permits in court more easily.”

● AR DEQ notes that “Land application [of biosolids] is pretty well accepted.” Some fast-growing areas in north Arkansas (e.g. Fayetteville, Bentonville) and around Little Rock see more complaints. The biggest pressures on biosolids management are costs borne by WRRFs for biosolids management, as well as regulatory and public pressures. Notably there is also pressure created by the need for upgrades and increased wastewater treatment capacity in some parts of the state.

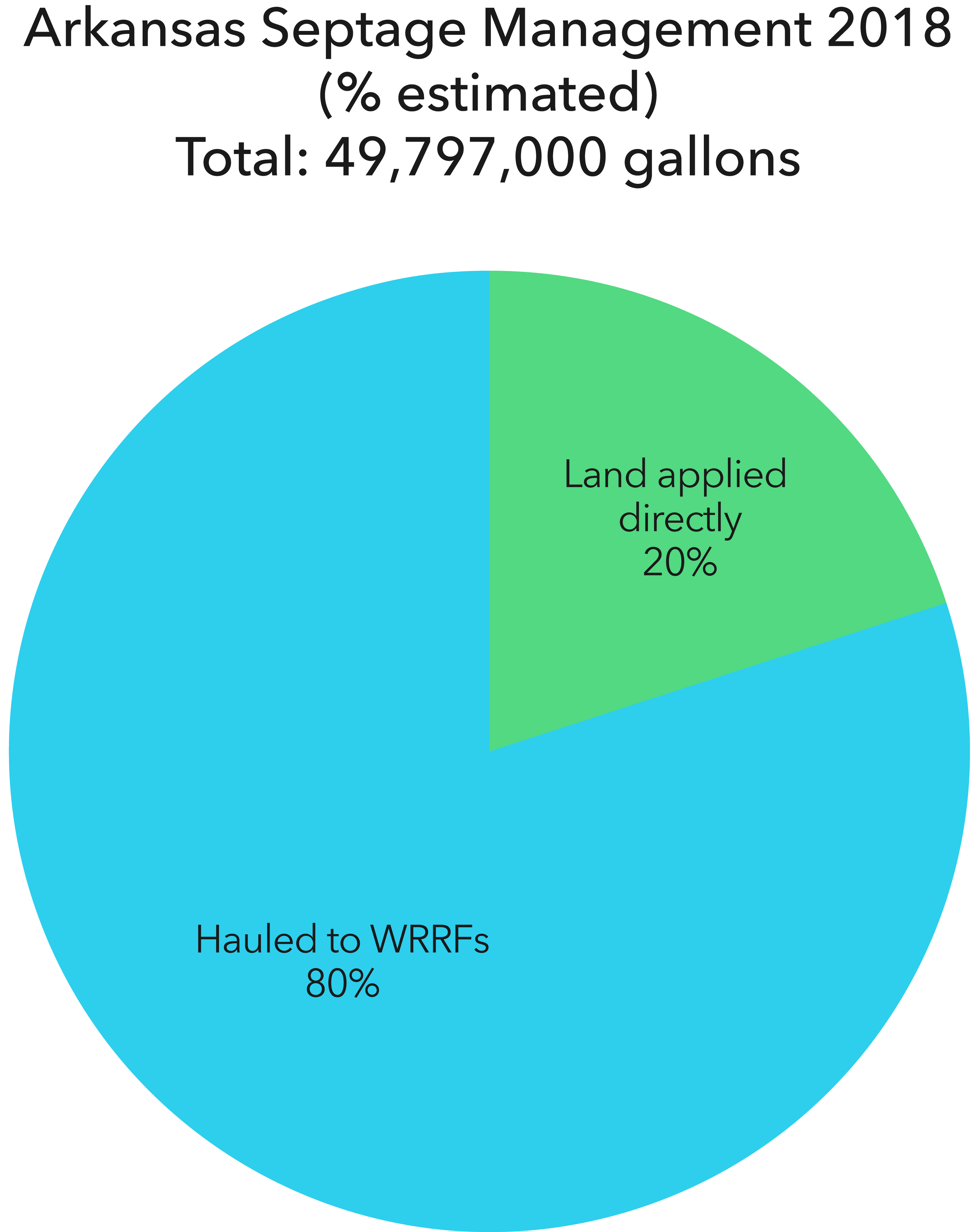

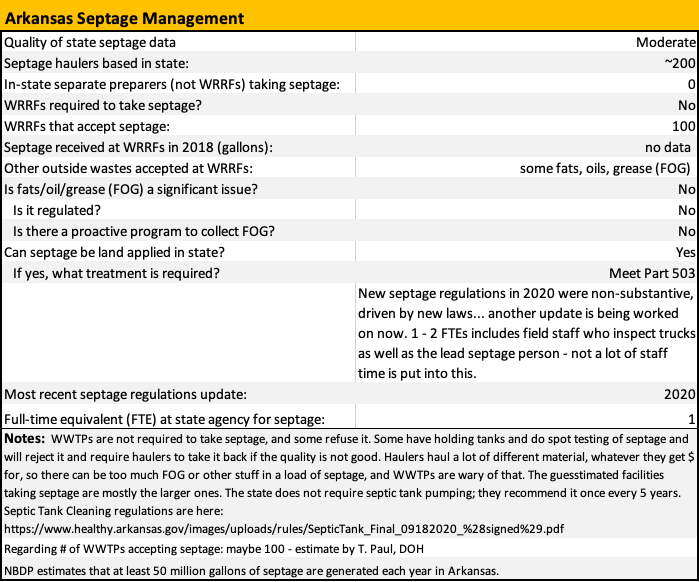

● About 1/3 of the state’s households rely on septic systems. Septage disposal and septic systems (anything less than 1000 gallons, domestic, individual homes) are regulated through the AR Department of Health (AR DOH). Larger tanks (>1000 gallons) serving more than 20 people are permitted by both AR DOH and AR DEQ. An estimated 100 WRRFs accept septage, and that is where most AR septage goes. However, septage land application is allowed and is done some.

● Little Rock Water Reclamation Authority owns and operates 3 water resource recovery facilities (WRRFs) for the state’s capitol and largest city (~195,000 population): Adams Creek (36 MGD design flow), Fourche Creek (16 MGD design flow), and Little Maumelle (4 MGD design flow). Solids from Adams and Fourche Creek are treated at the Fourche Creek facility in anaerobic digestion lagoons, generating renewable electricity used to power the facility. Those solids and the solids from Little Maumelle are all land applied in area agriculture. Little Rock has more than 300 acres permitted for land application, some for Class A and some for Class B or both.

● Fayetteville, the 2nd largest city in AR (~90,500 population), treats solids at its Biosolids Management Facility, which sits on 670 acres owned by the City adjacent to one of the two City WRRFs. The solids are dewatered with belt filter presses, dried in a solar greenhouse system, and then further dried in a heat dryer. The resulting Class A fertilizer is sold to farmers for ~$20/ton. Much is used on the farmland at the Biosolids Management Facility, mostly for growing hay. In early 2022, the heat dryer had failed, and a new one was being installed; in the meantime, solids were being landfilled at considerably higher cost.